Living: airbnb in Over-the-Rhine, Cincinnati, OH

Working: Platform 53, Covington, KY

Laundry: Wash Haus, Covington

This week in Laundry I Cincinnati.

There’s no other way to put it. My brief two days in this city, rich in history, architectural and otherwise, that straddles the Ohio river.

I straddle that river as well – as I live on one side of it, and work on the other.

Walking the streets, relics of an era predating not just the automobile, but the railroad, gives the first hints of the historied east coast I expect to encounter for the next few months.

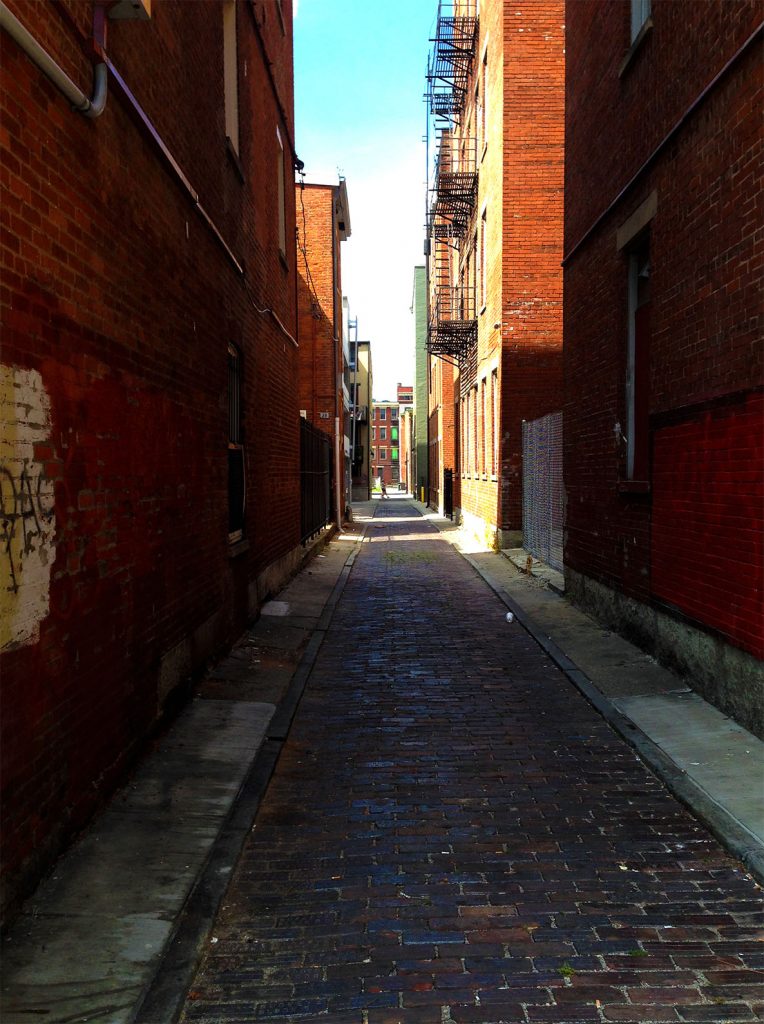

The narrow streets, some still paved in brick, evoke the older villages of Europe, or of older staples of eastern cities – Greenwich Village in Manhattan among them.

And the history around me unfolds not just by centuries past, but in an epic still writing chapters in the most recent decades, if not years.

When I looked to book in Over the Rhine (OTR), I knew only my briefly researched comprehension about a neighborhood densely populated in bars and restaurants, an expanding renaissance to the old brewery district, and a streetcar line so new, it’s first day of operation coincided with my first day in the neighborhood.

The ticket vending machines are still wrapped in cellophane.

What I didn’t realize was that OTR also remains a vibrant urban ghetto. A ghetto that block by block, aggressive development and urban planning meticulously crowds further and further to the north.

Drawing an almost visible line between OTR the gentrified, and OTR the ghetto. A neighborhood once rated the most dangerous in America.

This division was not clear to me when I booked my airbnb. It was not clear to me that I booked on the ungentrified, north side of this ephemeral line.

And to be fair, my block is just fine. It’s in the very beginnings of re-vitalization, or gentrification, by whichever name you call it. In fact, I saw a stroller dad exit his brick home this morning three doors down.

Four blocks south down a quiet street, and you’re in OTR proper.

Two blocks West, a shortcut to the brewery district and Findlay Market, and you’re in a whole different world.

Findlay Market has been in continual operation for nearly a century – through all forms of neighborhood

Which I did not realize until I was in the middle of it.

The markers, beyond race – it’s undeniable whilst in the neighborhood that this is a black neighborhood – reflect the hallmarks of an American urban culture.

Littered amongst the unrenovated, dilapidated, and boarded up housing – each building no doubt a historic German relic – lies the broken up concrete under a layer of garbage and debris.

People congregate outside in packs and groups. They lounge about in folding chairs, or stroll about in posies.

Each cluster brings their music with them, projecting Hip Hip, R&B and blues, depending on the particular cluster.

People idle purposefully, alone, on street corners.

And knowing, when I was in the middle of it, that the brewery district was just blocks away, I thought surely this urban culture of the street, in the sense of a people congregated out of doors, on the sidewalks, engaged in leisure, must give way. Both culturally, and racially.

What I didn’t realize was such a transition would be more akin to falling off a cliff than a gradual transition.

Cross the street, and instantly those that congregate the streets do so at the leisure of a café. They walk the sidewalks in smaller groups. There are strollers out amongst the families. The buildings are freshly renovated, well maintained, and virtually all of them occupied. There’s a farmer’s market. And yes the racial makeup changes from 80% black, to only 20% or so.

You just have to cross the street.

I’ve not seen such division, since perhaps the likes of New York. There I could believe the gentrification with New York prices coexisting in the relics of dangerous neighborhoods. But even then, I don’t imagine such divisions so strictly aligned on either side of the street.

This much is clear – my initial expectations for the neighborhood wholly fail in capturing the neighborhood in all its divided vibrancy.

And I had to know, what was the story behind these streets. What was the force that made this place this way?

OTR traces a past best described as the natural outcome of a series of economic incentives, lack of regulation, and personal agendas.

The neighborhood traces its roots to a time, before railroad, when canal systems stretched the eastern US, and European immigration was in full swing. The canal that swept Cincinnati from the Ohio river, up and through the city, and out to the Miami valley, formed a natural border.

It is here, just beyond the canal diving the neighborhood from downtown, the German immigrants created a small city to themselves, ever much in the colonial/European style of narrow roads and dense brick buildings. Here they created a community that would, through an odd combination of section 8 housing and urban anti-development, preserve the original brickwork in a collection of streets and homes that would become one of the largest single historic districts in the entire United States.

OTR isn’t the only german settlement in the area – just across the river in Covington, KY is the MainStrasse Village – and my coworking space for the week.

The Germans, in the reflection of the canal, would christen their home in homage to that great German river the Rhine. This is, then and now, a neighborhood just Over the Rhine.

Today the canal, not since needed at the advent of railroad, has been filled and paved. It is now Canal Street.

And the Germans have long been driven out – largely through anti-German resentment and hazing that occurred in Cincinnati during World War I. We owe to them the vast network of underground beer cellars and tunnels, designed to abate the common day law, as they built a small brewing empire here in OTR. In the very buildings the modern microbreweries, like Rhinegeist, now occupy.

Rhinegeist brewery and tap room – this building was once the bottling room of the Moerlein brewery. In 1895.

Even the Sam Adams brewery down the way serves as homage to the days of yesterbeer.

It was a series of economic coincidences that brought the neighborhood to become, in the early 2000s, one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in America.

First it was the interstate in the early 1940s, built with federal subsidies, that carved a route through Cincinnati, obliterating previous neighborhoods of poverty, and driving those residents into the adjacent neighborhood, long since vacated by the original German ethnicity. Then it was the section 8 housing credits, a federal tax program, that incentivized the growth of the area as a low income neighborhood. Which also meant a lack of incentive to invest in the now needed renovations. This coincides with the general trend of middle and upper class suburban migration further robbing the area of renovation incentives.

And finally, it was the agenda of a college educated man from a farm in the suburbs to keep the neighborhood undeveloped in order to ensure the poorest of the poor did not become homeless from lack of affordable housing, and that the homeless themselves need not be unattended.

It wasn’t until all these incentives became undone that the doors to change opened. Buddy Gray was shot dead in his office at the hand of a neighborhood resident, a mentally ill man he had befriended. The section 8 credits expired, all together. And as a general trend across the country, the young millennials were moving back into the cities.

As it turns out, a single corporate, not for profit, nongovernment entity by and large executes the meticulous, well planned, relentless, and incremental changes to OTR. Helmed heavily by the heads of the corporations that call Cincinnati home – Proctor and Gamble, Macy’s, and Kroger – themselves aware of the need to recruit new talent to their organizations, and therefore their city, coupled with the millennial urban migration trend, fuels a demand to create dynamic and engaging urban spaces in Cincinnati. If Cincinnati is attractive, working in Cincinnati for these corporations becomes so in turn.

These same organizations endow that corporation with the funds necessary to buy up blocks of property to kick start revitalization/gentrification, completely transform city parks, repour the concrete sidewalks, and fund new homeless shelters, away from the gentrification, to ease the vast amount of urban displacement from all the disruption.

It is an aggressive, subsidized, anti-freemarket approach to gentrification in response to the years of the aggressive, subsidized, anti-freemarket approach to anti-development and inner city preservation.

And it is because of the meticulous, block by block march of restoration and redevelopment at the well planned hand of this organization that such divisions of wealth and poverty exist in the neighborhood. Because there’s literally a line in someone’s urban planning map that draws the boundary between the block that remains the neighborhood of the past, and the block that becomes the neighborhood of the future.

And with each block marked by renovation, comes another block with urban upper middle class culture that reflects the buildings around them. Reflects the shops that go into those buildings. Reflects the people that inhabit those buildings. Reflects how those people use those streets.

And as that line moves further north, eventually it will run into the tall hills that encase the Ohio river banks and the city beneath. Those hills, conscious or not, create their own barrier. The march to claim the neighborhood for the upper middle class complete at the top of those hills.

All of this story behind OTR I learned from this article – I highly recommend it. It’s a fascinating span of history.

There are lots of things that make the article interesting from an economic incentives standpoint. For one, if the neighborhood had not been saved as a low income housing district, most of the buildings would have been razed in exchange for concrete during the redevelopment trends of the sixties and seventies.

Instead, buildings were simply abandoned and boarded up – remaining so to this day. In effect, preserving the original old world feel of the neighborhood at its height – if only waiting to be awaken from their deteriorating slumber.

OTR today, and the OTR that will become in the next decade would not exist in such a unique form without this.

And yet for today’s OTR to exist, it requires a quintessential mass eviction. The 3CDC does its part to minimize the hardship this causes. But that doesn’t change the fact that it’s doing it.

The story of Over the Rhine is a story of incentives nearly two centuries long. It is a story of cultural change and migration. Of clashes of classes. It is the story of If You Give a Mouse a Cookie, but in the real world, and anchored in a rich American history.

We respond to those incentives which provide us with opportunity to increase our wealth, status, or safety. We respond to those mechanisms which prevent us from unwanted outcomes, like incarceration, or poverty. We respond to those devices which grant us the things we value – which we value, mind you, not through careful and well-reasoned planning, but through our emotions. We are emotionally driven to attain such goals. We are guided to do so through the incentives we create for each other.

This is the principle which drives the world. We call it economics. We call it politics. We call it community. We call it markets. We call it complex systems. We call it Law. We call it love and hate and fear. We call it all of these things – it is the silent hand in each of our lives that drives us to make decisions based on the decisions that other people have made. And in response to the will of the earth, mother nature.

As for me, once again, my immediate goals are met. My laundry, for this week, is finished. And my decision, in this moment, is to bid adieu. Until the next wash, my friends.

Deby August 11, 2016

Another fine article, Andrew.

Did you have some Cincinnati Chili while you were there? Hadley says it is quite good.

Andrew August 12, 2016 — Post Author

I haven’t yet! I can’t remember how I first heard about skyline, but I’ve known about it for years. I drive by two or three on my way to work alone. I’m probably doing Queen City Cinci wrong if I don’t go at least once!

Janice Hixson August 12, 2016

I have always wanted to go to Cincinnati and now I really want to.

I have a dear friend, Mary, who lives there. You know her but you were really little.