Living: Airbnb in Garfield, Pittsburgh, PA

Working: Catapult Lawrenceville Pittsburgh

Laundry: Butler St Coin-Op Laundry, Lawrenceville

This week in laundry I play rules and break games.

In my younger years, long since past, I used to play a game.

I’d walk into a bar, have a drink, walk up to a perfect stranger, and ask them to send me to another bar.

Following their recommendation, I’d make my way to the next bar, and then repeat the cycle until the night was through. Often to 2am or later.

Through this game, I came to explore the city of Chicago. I finally found where all the kids my age were hiding in the city. I stumbled across the vast Chicago Lit scene. I found the drummer for the Sueves, before they played their first show ever. And I would eventually find a friend on the south side of Chicago. A year later, that friend founded a punk poetry workshop. That workshop birthed the Warsaw Vices, my former band.

All of these things, so important to my Chicago life and identity, exist as a result in one form or another of playing a game.

I am a shy person by nature. This is in addition to being fairly introverted. Under normal conditions, I would be unlikely to approach a stranger. It’s simply not in my nature.

I see these impediments – which exist strictly within my mind – like lines in the sand. Lines that feel like brick walls. I cannot cross them.

Trying to tackle them by brute forces feels much the same as heading head on to concrete.

And if you were to label these things – these lines, these walls that exist only in my mind – what would you call them? They are, most certainly, a force of imposition. If they were not, I would not feel a struggle against them.

But neither are they laws of nature – it is not as if these lines were gravity – unavoidable. Or as if they were impenetrable – bound by Newtonian forces.

So I call them much the same as we call many boundaries created only within our minds – be it implicitly, through social agreement, or by cultural norms. I call them rules.

For this is what rules are – they are restraints to action that exist not through restrictions imposed by nature, but through the limits imposed by people. They exist through social contract, through culture, through example. The exist only in the mind.

Sometimes such rules are overt. They are dictated by governments, and imposed by systems of organized enforcement. We call these rules laws.

Sometimes such rules are implicit. Like laws, they are culturally relevant. But they exist silently – learned through social behaviors. These are rules that exist because, simply, it’s what everyone else is doing. We might consider transgressions against these rules as rude, impolite, and disrespectful. Violation may result in stern looks, or ostracization.

Often such rules are not documented. They exist through collected cultural knowledge. They might vary regionally in both minor nuances or major differences.

Other times, though undocumented, they might be explicitly taught. I’ve more than once heard “it’s rude to point” – not just in the family, but through different media as well. Why is it rude to point? Is this a law of nature? Not quite so – it’s a cultural standard. It is not a law of government – it is a rule circulated, standardized, imposed and taught through common culture.

In many ways culture exists through such rules. These rules govern the local, cultural definitions of beauty – of beatification. Of clothing. Of sanitation. Of holidays and celebration. And yes, even the appropriateness of routine laundry.

For example, I’ve found an implicit rule here in Pittsburgh on how people great each other. Universally they ask “how are you?” Universally, you ask the same after your response. This is not the same elsewhere in the country. But this is the overwhelmingly obvious rule at play at the forefront of just about every social interaction I’ve witnessed. Or participated in.

Culture is undeniably a fundamental component of being human. And if culture is so intertwined with rules – with those things which define the culture uniquely – then rules must also be a fundamental part of being human as well.

And to someone who feels such rules – simple lines in the sand – as impenetrable brick walls – this seems undeniable. Rules are a central component to the mind. Rules, as much as music, communication, collaboration, and competition, live in the human mind as a mechanism that defines, guides, and shapes human behavior and experience.

I’ve spoken about play before, much in the context that story is a form of play. And by larger extension, play is a mechanism that humans – as well as other animals – engage in as a form of learning – as a way of trying to figure out the world around them. It has pleasurable qualities associated with it – and as such we are incentivized to attempt to learn the world.

Part of that learning goes towards trying to understand the laws of nature – the immutable behavior of the world around us.

Parts of that goes towards learning the laws of man – the rules, both implicit and explicit, formed by the world around us.

And play itself is very concerned with rules – because in play, the rules change. We impose new rules – the rules of a game – or we change the rules of the world around us – to allow for experimentation against those rules without the true consequences outside of gameplay.

These are the mechanisms at play in a game of joust – the practice of a skill of war, without the consequence of war – in the context of a game.

Jesse Schell, of Imagineering, CMU ETC, and Schell Games fame, wrote a book several years ago on gameplay – The art of game design, a book of lenses.

The book tackles the concepts behind game design – a sort of entomement of Jesse’s ETC instruction. Early on in the book, Jesse wrestles with the question “what is a game?” and in it, addresses the question “what is play?” coupled with a back history of research and philosophy.

Jesse works his way through several attempts to arrive at his solution – which I won’t spoil. Go and pick up the book if you’re curious!

All games are a form of play, but not all play is gameplay. This seems intuitively true, but under careful examination this might not entirely be so.

A defining characteristic of play is that it has something to do with not the real world. It may imitate the real world, manipulate concepts of the real world, simulate the real world. But it is not the real world.

There’s a shift in consequences in play. It’s a necessary characteristic of the quality of play that serves a purpose – to learn through manipulation – through experimentation. If somehow the consequences are different. Or the manifestations are different. Or the defining characteristics of the world are different. Instead of engaging things as they are before us – the real world – we engage things as a representation of something else.

In general, a definition on play is highly contested in the academic world. But undeniably, the thing that makes play play is its differentness. When play happens, something has to change in the way we engage our brain as we activate the play mechanism within it. We are thinking about things differently – approaching things differently – when engaged in play.

But what’s changed? Other than, clearly, our brain chemistry in the activation of that play mechanism? The laws of nature haven’t changed – not outside our heads at least. Though inside our heads, we may manipulate those rules. The rules of people haven’t changed – the culture is still the culture.

It’s something inside us that’s changed. Something inside us about the way we approach or consider things. It is those things called rules, which exist only inside us, which we temporarily modify in the context of play.

And it is the brain chemistry behind play that allows us to do so.

This is why, through gameplay, I so easily overcome those brick wall impositions. Those rules that, beyond my conscious will, prevent engaging in conversations with strangers. By shyness, or introverted nature, or Pavlovian learned behavior, whichever inner mechanism instantiates these rules, it is through gameplay that I easily work around them. It is through gameplay that I activate the mechanism within my brain that allows a change of rules.

One of the qualities of gameplay – a quality that shows it a true cornerstone of the human condition – is the ability to detect when others are engaged in play. It is through this mechanism that we allow each other to engage in play. And if we are willing, we allow the violation of those social rules for the individual engaged in play.

When we allow this to happen, we engage in play with the individual.

When we do not allow this to happen – when we continue to enforce the standard set of rules – there is discord. For one person engages in play with one set of rules, another remains out of play, with a different set of rules. Such a discord often leads to very complicated conflict.

I find it fascinating though that, in general, we can tell when someone else is engaged in play. If we disallow that engagement – if we don’t engage ourselves by at least allowing the modified ruleset at play – we generally do so not in ignorance to the other’s engagement in play, but in conscious opposition to it.

This isn’t always the case – many a misunderstanding might arise by not catching the play signifiers. But in general, as people, we can tell. We might not call it play – but we can tell that there’s a quality of otherness – a quality of this doesn’t count.

This ability to tell when others are at play is the largest piece of evidence that play is, in fact, a true condition of the person.

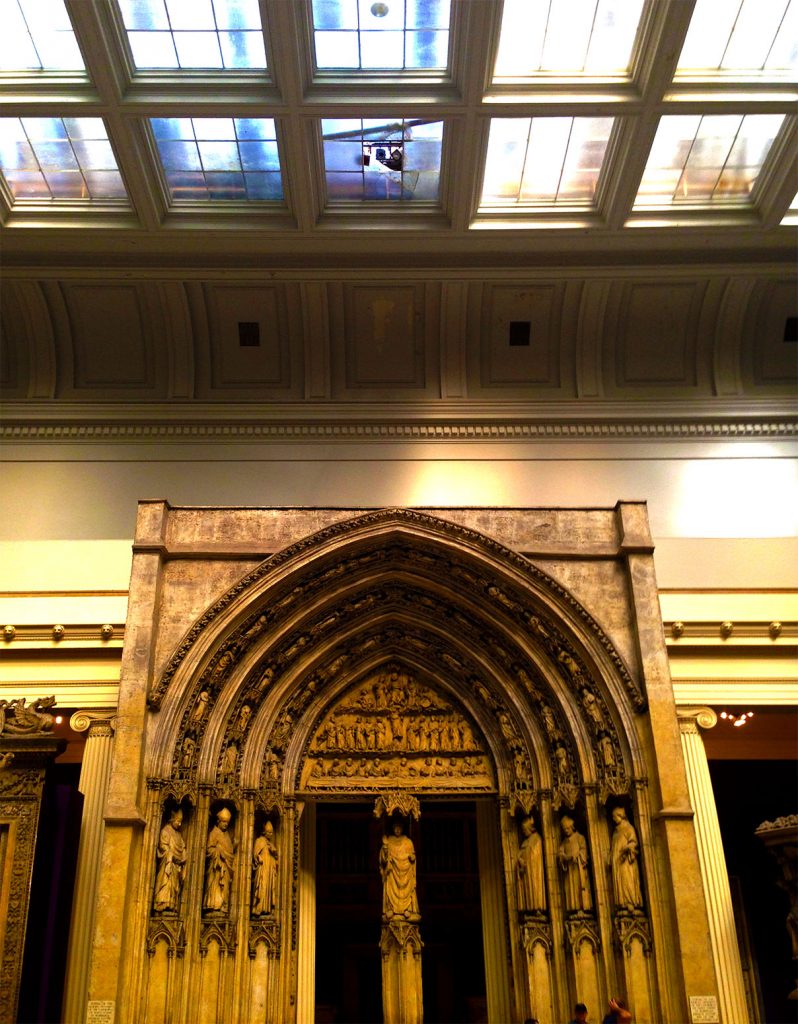

And when they’re actors in a play, it’s really obvious. The play stages of the Stephen Foster Memorial in the shadow of the Cathedral of Learning at Pitt

The Carnegie Mellon Software Engineering Institute – a block down the street from Pitt’s iconic Cathedral of Learning. What rule says you can’t put two major universities side by side?

But beyond play in the manipulation of rules, rules have a good deal to do with the way we behave as people, both by the laws of government and the rules of culture.

Michelle Foucault, the French philosopher, explores the nature of these rules – how they manifest in our behaviors – how we instantiate them against each other – through the concept of the panopticon.

The panopticon was an 18th century style of prison construction. At the center of the prison a central structure houses a guard. Prison cells are stacked one after the other circularly around the tower – each cell is missing a wall, exposing the cell to the view of the guard.

At any given point in time, the guard is capable of peering into any cell. At any given point in time, the imprisoned must consider that they might be, in this moment, under surveillance.

However, there are too many cells, and not enough guards, to monitor all inmates at the same time.

So at any point in time, each prisoner faces a risk of being under surveillance. Should the prisoner act counter to the rules and regulations of the prison, that prisoner faces a risk of being caught – simply because the prisoner may be under surveillance – and the prisoner cannot know if at any given moment they are being watched.

And while the panopticon was invented as a prison of 18th century origin, Michelle Foucault extends the concept to society on the whole. In each our daily lives we are monitored – or may be monitored (we do not know) by the others around us. And if monitored, and caught acting counter to those rules, explicit (laws) or implicit (social norms), we face a risk of retribution. We feel this inherently, and conform to such rules often without explicitly thinking about it – the panoptic principle at play, each to each other – as an ingrained mechanism of the mind.

We call this social theory panopticism.

Through such mechanisms – the risks of being monitored, the risks of retribution – we can find a study in behavior economics – decisions people make based on risk. And in general, counter to a fundamental theory of economics that all individuals are rational actors, people make decisions in response to the decisions made around them often in irrational ways – but often in predictable ways according to the general mechanisms of the mind. Behavioral economists, such as Dan Ariely or Daniel Kahneman, have been studying this for years. Although it’s only recently that this study of pseudo-economics and psychology has gained prominent acceptance. Including a nobel prize.

And wherever there are rules, we can find understanding in games. In this case, in the general study of microeconomics known as game theory. Such as the Nash equilibrium. Or the prisoner’s dilemma – a comparison of risks and rewards in the decisions of cooperation and competition. And like Foucault points out in his analogy – the prison is everywhere. The risk of retribution in any action, potentially counter to those rules abroad, all enforced through the judgement and actions of others.

Even laws, those explicit rules written by the large social institutions called government, function strictly by the behavior of our peers. For our peers must first indict us. Then our peers my try us. Then our peers by jury of twelve must convict us. And even once the conviction is through, a peer – a judge – must sentence us. And once that is through, peers – the bailiff and the sheriff – must force us to those sentences. At all points our peers operate by their own free will. And at any point they may disagree on the nature of the rules. Or their actions may neglect a set of rules all together – for another implicit set. Or they may simply act by their own unique volition.

And while we may fail from time to time to acknowledge those implicit social rules and constraints, or fail to recognize or understand their mechanisms at work within our head, we manage to find ways to reflect upon them. Like the phrase think outside the box. What does that mean, exactly? What is the box, and why should we think outside it? Why, as is implied, do we usually think within it? Is the box a form of human nature that we must consciously combat through acknowledgement in idiomatic phrases?

The box is built of rules. The rules explicit and implicit that guide our behavior. The rules that somehow work in the context of the clock of our mind. And it is so strong and so fundamental to how we operate, that we must encourage ourselves to work beyond those restraints. We encourage ourselves to work beyond those rules. Beyond those lines in the sand. To move beyond the brick walls we call the box.

I think this represents one of the values held by successful startups – and why the ethos of the startup brings so much innovation in the shadows of larger established organizations. The capability to be disruptive – and the vision to see the rules as they are, and understand when to work around them.

Some of these rules may be social – that you shouldn’t start a company at the onset of such risk, that you shouldn’t strive to achieve great and difficult things – that you should fall in line for the status quo, and be happy to do so. The people who make startup entrepreneurship a cornerstone of their life – and really when you’re in startup mode it consumes the vast majority of your life – break such rules with a vengeance.

Others may be more overt. Like uber or airbnb. These companies operate, or encourage operation by their members, often in opposition to established laws favoring safety in the taxi or hotelier industry. They are often told to shut down, or governments put new regulations in place to address or limit their practices. These companies have moved into billion dollar valuations in the spirit of operating not within the law, but where they feel the laws should be in our modern, connected, and fast moving world.

These companies are disruptive. And they aim to disrupt. Their disruption sets sights on the rules, both explicit and implicit. It is in the understanding of how these rule mechanisms work, and how to work around them, that startups see the insights necessary to innovate – by blowing through brick walls. By blowing through lines in the sand. By blowing up the boxes.

In some ways, operating as an early stage startup is a form of gameplay. It’s not a true form of play – because the risks are real. Failure has real costs – the experimental qualities of play are not wholly present.

And yet, there’s a special other-worldliness when you’re in startup mode. A sense that the rules that were no longer apply. There are new rules here. Rules of low-cash living, of apartments shared by co-founders that also serve as headquarters. Rules of forgone social lives. Rules of the incubator. Rules of the venture capital culture. A new rule of what it means to see value in yourself – all in the effort, at high risk, of building something amazing.

It is like a game, lived fully, because it is the temporary adoption of a different and distinct set of rules, set to serve the achievement of a specific set of goals. These are a defining quality of startup culture and life. These are the defining qualities of games.

And much like the startup entrepreneur, I live at the moment by a different set of rules. My life by any normal cadence has been disruptive. There’s no other way to describe picking up and moving on every one to two weeks.

Whatever implicit social rule that says, your home exists within a large established community, and your career must be made in the shadow of that community, I eschew completely. The communities I find I penetrate one week at a time. Pittsburgh’s no exception – I’ve really enjoyed being a part of the Catapult community. No matter where I am, my career flourishes. Wherever there’s an internet connection, there’s productivity. Achievements build daily.

And I don’t really know what home is anymore. But I know what it feels like to belong. Because for the moment, I belong to the road. And it belongs to me.

As I touch it, breathe it, see it, through each week in laundry.

By now I’ve long since packed my dry clothes away. And soon, Butler street, and this laundromat on it, will be but a memory. This is by far my longest post to date. But then again, there is no rule that guides the general length of my weekly wash in writings.

By the time I unpack for next week’s laundry, I will have seen the ocean once more – a different ocean from the one before, as I reach for the east coast in Portland Maine.

Deby September 10, 2016

I always learn a little something I didn’t know before. Thank you, Andrew!