Living: Dallas

Working: Texas

Laundry: Main Street District

This Week in Laundry I consider what film editing can teach you about business.

I’m back in Dallas. As my team continues to work towards the grant submission due this Wednesday. The website’s up.

And I have a first cut in hand for the video portions.

The edit’s as good, if not better, than what I had hoped for. It’s speaks strongly to the team’s video guru.

Dillon’s Cut of the projection mapping demo.

Part of what makes the cut so good is not what’s there, but what’s missing.

I was on location during the shoot. So I know what footage we got. And what pieces we spent the most time on.

There’s a lot that’s really working in the edit. The flow of motion. The motif of movements. The moments, quite like breath, of inhale and exhale.

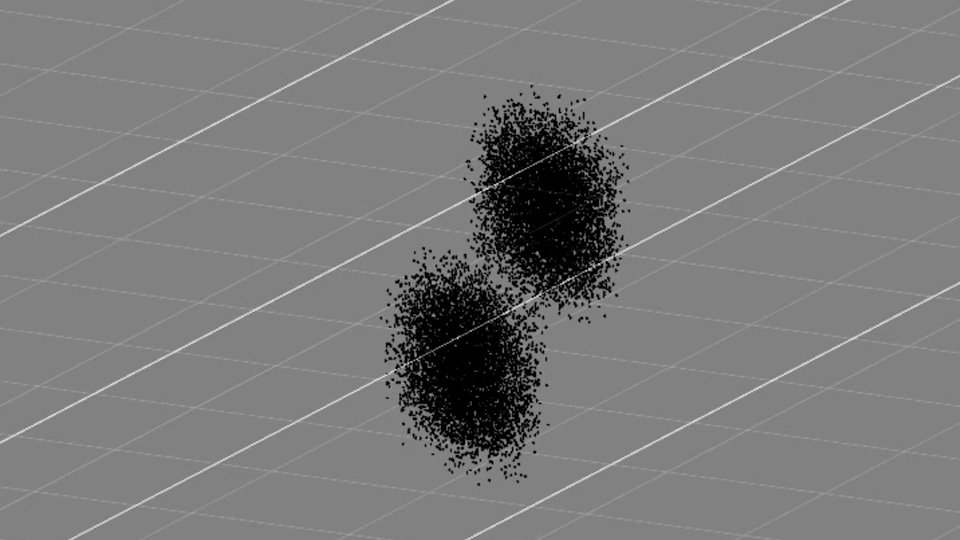

Using the unity3d mesh preview as a part of the particle breath motif – combined with a sort of match-on-action

They all come together to tell a story about the particular piece of technology we would like to use in this grant.

So in the midst of everything that’s working, it’s easy to overlook everything that’s not there. Whole chunks of shot footage left somewhere on the editing room floor.

In fact, if you weren’t in the room for the shoot, you wouldn’t even know anything was missing.

That’s because it’s not missing. It’s just not present.

This demo shines as a great example of what an editor does. Why having an editor apart from a writer/director can create so much value.

The editor’s job is to take the resources she or he has available – raw footage, constraints on edit time, available audio – and construct the best possible product from it. To that person, it doesn’t matter how long it took to setup shot x, or how difficult the lighting was in shot y. It’s the final output that matters, and the editor will use whatever shots, tools, and resources at his or her disposal to execute that output.

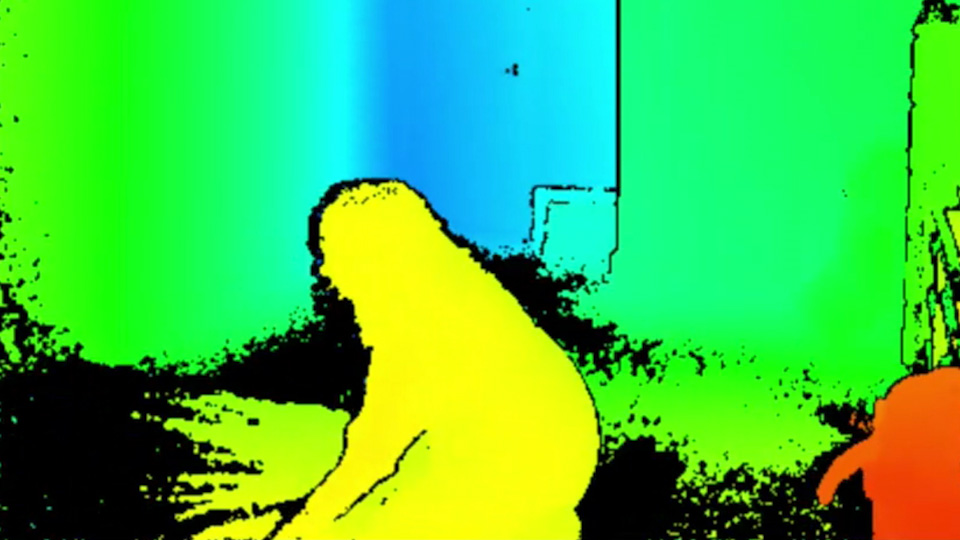

A color render of the kinect depth buffer – one of Dillon’s available resources when constructing the edit

Sometimes that might take an extreme form. Documentary editors often completely re-organize footage in order to find a relevant story within. That’s what I remember Andrew Dickler, editor for Anvil, the story of Anvil, talking about at the Wisconsin Film Festival during my undergrad.

Sometimes that’s less extreme. Maybe a whole scene gets dropped from a feature production – even if that scene cost a couple million dollars to shoot in time and materials. Maybe a painfully choreographed long take needs to be cut up with insert shots for pacing or information. Or cut in half. Or maybe a long shot isn’t working and closeups – much easier to light and shoot – are used instead.

In the editing room, the past is the past. The editor doesn’t care. Can’t care. Because the only measurement the editor should care about is the measurement made against the final product. And the final product isn’t about how something came to be. It is what it is. So the editor must make the best is possible in any way possible with whatever he or she has to work with.

I know this. I’m familiar with it. It’s something I learned in film school. It’s the same principle that underlies the notion that good writing is mostly re-writing. Because once something is written, there’s no value in the effort made to write it. There’s only value in how people feel about the written work. And sometimes that means going back to the drawing board. Or writing notebook. Or editing bay. Depending.

After seeing Dillon’s edits I now realize that these principles that underlie creative construction – namely the willingness to throw away the unnecessary – are the same principles at work in overcoming sunk cost bias in business.

We spent most of the shooting time on this sequence – an actress walking up to the bed. And yet, this shot remains as only a small portion of the overall cut

I’ve written about this bias before. It’s the tendency to overvalue money spent or work performed. And any decent MBA will warn you about this bias. Because ignoring it can lead to a cascade of poor decisions in the wrong direction as a result of the first decision made.

In this sense, great editors behave like great business executives. They care about the best output they can create in the moment, based on the resources available. They don’t place value on resources already consumed – time spent writing, lighting, shooting, and producing. If the cheapest shots are the ones that work best, use them.

I imagine this quality isn’t limited in editors alone, but in all kinds of creatives. Writers, designers, musicians, and even lowly software developers. Sometimes you need to cut the fat. Sometimes you need to throw the baby out with the bathwater. At least I think that’s the English idiom for this act. If that’s what it takes to achieve the best possible result given the available resources, then that’s what it takes.

I’ve certainly thrown away huge chunks of code before. Weeks of code. Sometimes you have to during refactoring, or when a new requirement comes in that invalidates a past architecture.

And I’ve certainly thrown away a lot of writing. Especially script writing. Tons of footage as well.

It can be hard. Most people’s first instinct is to defend the work they’ve done. I remember this especially during film school – my first moments of creative criticism. It’s easy to get defensive and hurt.

But great creatives listen to feedback. And try to understand the source of the feedback. That feedback comes from somewhere – if it didn’t, then the person giving that feedback wouldn’t say it. The trick is often filtering through the feedback. Not everything applies directly.

But it’s important to not just hear the feedback, but to listen to it. To digest it, understand it. To try and dig at the source. I find, very often, this exercise provides new insights.

I once overheard that an MFA is the new MBA. And maybe this is why. Or at least one of the reasons why. Because the creative process is all about digesting feedback and leveraging it based on available resources. An MFA candidate executes on this throughout his or her graduate education. And this is the key behavior in great enterprises focused on moving forward – on achieving goals given the resources available.

So do I think every executive should go to film school? Yes actually. Because that gives me a head start. But I don’t think they will.

Short of that I think the most important thing we can do is to listen to ourselves. Listen to the moments we get defensive. Pay attention to these moments during feedback or criticism that brings about a defensive response or behavior.

There’s a reason that behavior exists. It’s only human. But it’s also a red flag that sunk cost bias may be blinding our perspective. Preventing us from seeing, learning, digesting, and growing from very important information.

That may require taking that feedback and putting it in your back pocket. To mull over, freely, at a later time. When you’re less prone to get defensive.

And if you find yourself short on time to do so, just remember – at least there’s laundry to look forward to. In the cycle of the wash and try, perhaps you might find that moment to absorb that feedback. Or to discard the past. Or forget the costs of filming. A moment to simply look at where you are and what you have. And then, use it for the future.